Role of Private Sector in Higher Education

There are three levels of education; elementary, secondary and higher. The first two are imparted at the school level, whereas higher education is imparted at the college and university level.

There may be two types of providers of education: public and private. Private institutions may be partly funded by the government (aided) or entirely self-funded (unaided). Public institutions are established, funded and managed by the government. Private providers of education often step in when the government has limited resources to provide universal access to education. In most markets, the private sector is characterised by a profit-motive. However, when it comes to education, the private sector is required to operate on a not for profit basis.[1],[2]

Some experts are of the view that certain private providers of education dilute the quality of education due to a lack of regulatory oversight and restrict access due to charging high fees from students. On the other hand, some consider private involvement to be necessary to enhance investment and quality, as a result of increased competition, in higher education.[3],[4]

The Standing Committee on Human Resource Development is currently examining the subject ‘Role of Private Sector in Higher Education’. In this context, we present an analysis of the role of the private sector in providing higher education in India. This note maps out the regulatory framework and highlights key issues with regard to private higher education.

Regulatory framework

Constitutional provisions

Education falls under the Concurrent List of the Constitution.[5] This means that both the centre and states can enact laws related to education. In addition, the mandate of determining standards of higher education and research lies with the centre, as this falls under the Union List.[6] Further, states have powers to incorporate, regulate and wind up universities as a subject under the State List.[7]

Administrative framework

At the centre, the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) formulates policies, and implements laws and schemes related to education in the country. Under the Ministry, the Department of Higher Education is responsible for the higher education sector. At the state government level, Departments of Education carry out similar functions. Institutions offering specialised professional disciplines in sectors such as health, agriculture, etc, are regulated by their respective ministries.

Regulatory bodies

The main regulators for higher education are the University Grants Commission (UGC) and the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE). In addition, there are 15 professional councils regulating various professional courses. These are statutory bodies established by Acts of Parliament such as the Medical Council of India, Bar Council of India, Council of Architecture, etc.

Types of higher education institutions

Table 1 shows various kinds of higher education institutions that may be established:[8]

Table 1: Types, examples and number of higher education institutions in India

|

Universities |

|||

|

Parameter |

Universities |

Institutes of National Importance |

Deemed Universities |

|

Setting up |

Set up by an Act of Parliament or state legislature. |

Declared as such through an Act of Parliament. |

Status given by the central government on the recommendation of the regulator, the UGC, which bases its recommendations on the findings of an expert committee. In case of declaring technical institutions as deemed universities, the AICTE advises the UGC. |

|

Nature and scope |

Empowered to award degrees and affiliate colleges. Private universities cannot affiliate colleges. |

Empowered to grant degrees. The Constitution provides for institutions imparting scientific or technical education, financed by the central government, to be declared institutions of national importance.[9] Each institute is governed by their Act. |

Empowered to grant degrees. They can institute campuses in the country (in parts other than where the first campus was set up) and outside. These institutions offer advanced level courses in a particular field or specialisation, with a focus on post graduate studies. |

|

Example |

Delhi University is a public university and Amity University in Uttar Pradesh is a private university. |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT), National Institutes of Technology (NIT), etc, which are governed by the AIIMS Act, 1956, IIT Act, 1961 and NIT Act, 2007, respectively. |

Tata Institute of Social Sciences was granted the deemed university status in 1964. |

|

Number |

As per All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE), there were a total of 665 universities in the country in 2014. |

Presently, there are 73 such institutes in the country. |

There are 127 deemed universities. |

|

Colleges |

|||

|

|

Colleges |

Stand-alone Institutions |

Autonomous Colleges |

|

Nature and scope |

These may be public or private institutions that do not have the power to grant degrees. To be able to grant degrees, they are required to be affiliated with public universities. |

These are institutions or colleges (not affiliated with universities) which cannot award degrees and may run diploma level programmes. |

Determines own curricula, teaching, assessment, examination strategies, etc. Remains under aegis of a university for the purpose of granting degrees. Status of autonomous college is conferred by UGC, on the recommendation of an expert committee, in consultation with state government and university concerned. |

|

Example |

St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. |

District Institutes for Education and Training. |

St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai has been an autonomous college since 2010. It grants degrees under the aegis of Mumbai University. |

|

Number |

According to AISHE, there were 36,812 colleges in India, in 2014. |

Currently, 11,565 stand-alone institutions are functional. |

There were 487 autonomous colleges in India, till December 2014.[10] |

Sources: “AISHE 2013-14 (Provisional)”, MHRD, 2015; “Report of the Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) Committee on Autonomy of Higher Education Institutions”, MHRD, June 2005; UGC; AICTE; PRS.

Establishment of Private Universities

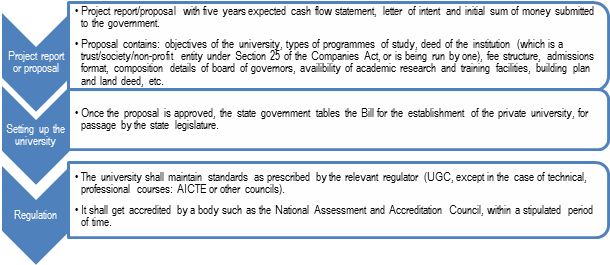

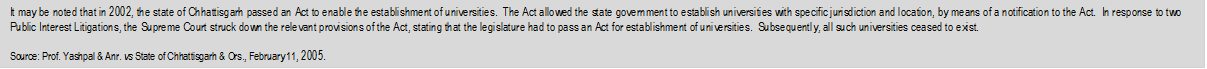

A university must be a trust, society, not for profit entity or should be run by one. There are two routes to establish a private university. Primarily, it may be set up through an Act of Parliament (central university) or an Act of a state legislature (state university). Till date, no private university has been set up through an Act of Parliament. The other route is by being declared a deemed university. Currently, 229 universities are privately managed.[11] States may differ in the land norms and other procedural steps required in setting up a private university. However, an analysis of laws in some states such as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat shows that largely these requirements are similar across states.[12] An example of the requirements for setting up a private university in the state of Haryana is provided in the adjacent text box.

Procedure to establish a private university:

Other routes to establish a private university through the central government:[13] An existing private institution/college may be conferred the title of a deemed university in the general or ‘de novo’ category. Under the general category the institution should: (i) have been in existence for at least 15 years, (ii) be engaging in areas of specialisation and not conventional degrees such as engineering, management, etc, (iii) have undergone external accreditation and assessment, (iv) possess the necessary infrastructure for quality research and have modern information resources, etc. Symbiosis International University, Pune has been declared a deemed university through the general category.

Under the ‘de novo’ category, the institution must be devoted to unique and emerging areas of knowledge, not being pursued by existing institutions. The Ministry may notify the institution as a deemed university under the de novo category on completion of five years of the institution as such. The Energy and Research Institute (TERI) acquired the deemed university status through this route.

Funding for universities remains unchanged once they are declared deemed universities. Deemed universities may be allowed to operate beyond their approved geographical boundaries and start off-campuses (additional campuses within the country) or off-shore campuses (outside the country). They may also conduct joint programmes with other universities, or deemed universities, in India and abroad.

Note that no institution has been declared a deemed university since 2009. The centre derecognised 44 universities in January 2010 as they were found to be deficient on several counts such as lack of infrastructure, disproportionate increase in intake capacity, high fee structures, little evidence of efforts in emerging areas of knowledge, etc. The centre’s move was appealed to the Supreme Court by the universities.[14] However, the Court did not reverse it and left the final decision with the UGC.

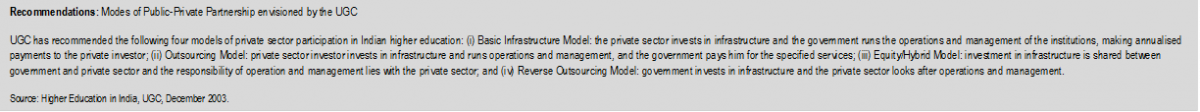

Regulation

The UGC has powers regarding the recognition, functioning and de-recognition of deemed universities. It is also empowered with disbursing grants to other universities for their maintenance and development, and with regulating fees charged by universities. Failure to comply with UGC standards may result in withdrawal of grants or termination of affiliation of a college to a university, if the college does not comply with fee and other regulations.[15] Private universities offering technical courses such as engineering, town planning, management, etc, and receiving funding from AICTE, are required to comply with its academic standards and regulations.[16]

Key issues and analysis

In this section, we analyse a number of issues that exist within the higher education sector in India, with a special focus on the role of private players.

Supply

For-profit educational institutions and private players

Private providers are typically driven by a profit motive, but over the years, the Supreme Court of India has interpreted the nature of educational institutions to be charitable and not for profit. Therefore, supernormal or illegal profits cannot be made by providing education. If a revenue surplus is generated it is to be used by the educational institution for the purpose of its expansion and education development.1,2

The National Knowledge Commission (NKC) was set up in 2005 to give recommendations on building a knowledge base in India, including reforms required in the education sector. NKC did not encourage for-profit educational institutions.3 The Yashpal Committee was set up in 2008 to recommend changes to the higher education sector. It also suggested that private providers of higher education should not be driven by the sole motive of profit.4 However, both NKC and Yashpal Committee recommended that it is essential to stimulate private investment in higher education to extend educational opportunities. This aspect is further discussed in detail in the issue of access, under fee structures.

There are many private, not for profit higher education institutions that have been operating in countries like the USA for many years such as Stanford University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, etc. Alternatively, the University of Phoenix in the US is private and for profit. The UK higher education system is also characterised by many private providers, which operate on a not for profit basis.

Demand

Access

Enrollment:

Low enrollment: The total population of India is currently 121 crore.[17] Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER) is calculated as a percentage of total number of students enrolled in a specific level of education (higher education in this case) divided by the total population within the relevant age group (18-24 years). In 2013, the GER for higher education ranged from 14%-24%. The GER for higher education differs on the basis of two official reports for the same year, the Ministry’s All India Survey on Higher Education (24%) and the Standing Committee report examining the Demands for Grants of the Department of Higher Education (13.6%).11,[18]

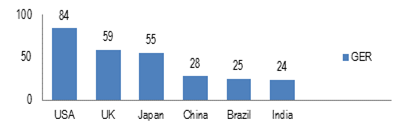

In India, GER in higher education has more than doubled over a period of 11 years, going from 9% in 2002-03 to 24% in 2013-14. The Rashtriya Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan is a centrally sponsored scheme launched in 2013, mainly to provide funding to state higher educational institutions. The scheme’s objective is to achieve 30% GER in higher education by 2020. While GER has increased, it reflects that currently only 24% of people who should be enrolled in universities (as per target age-group of 18-24 years) are actually enrolled. This is fairly low compared to other countries such as the UK and USA, as seen in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: International comparison of GER in higher education in 2014

Sources: “Demands for Grants of Department of Higher Education”, Standing Committee on Human Resource Development 2015-16; PRS.

Expected increase in demand for higher education: The GER for elementary education is over 100%. For secondary education, this ratio is over 50%. As enrollment in elementary education has been maximised, and enrollment and drop outs in secondary education are being addressed, the pool of students seeking higher education opportunities will increase over the next few years. Therefore, there will be a greater demand for university education. The NKC recognised that government financing cannot be enough to support the massive expansion in the scale of higher education.

It may be noted that over the past 10 years, the central government expenditure on higher education, has been fairly constant around 1-1.5% of its total expenditure.[19] While various committees have observed the importance of private sector investment in higher education to raise this expenditure, there is no data available on private sector spending in this sector. Currently, India spends 1% of its GDP on higher education. In contrast, USA spends about 3% of its GDP on higher education, Canada 2.5%, Chile 2%, Russia 1% and Brazil 0.5%. USA, Chile and Korea also show high proportions of private expenditure on higher education (between 1.7% to 2.1% of GDP).[20]

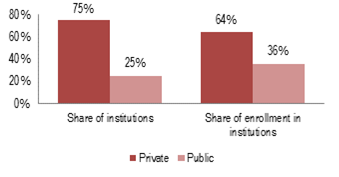

Data indicates that currently the private sector is playing a significant role in addressing access to higher education. As on 2014, there were a total of 36,812 colleges. Of these, 20,390 colleges were private and 6,768 were public colleges.11It may be noted that these numbers (and data represented in figure 2) are not reflective of the number of seats available in public or private institutions, and how many seats are filled or vacant. In addition, regulatory requirements to set up universities may vary across states. This could be another factor for some states having higher enrollment in public/private institutions as opposed to the other (in table 2).

Figure 2: Enrollment and percentage share of unaided private institutions in 2013

Sources: AISHE 2014; PRS.

At the state level, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu are states with the maximum number of colleges, followed by Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat. These states also consist of the highest number of private colleges. Details of all states can be found in the Annexure.

Types of disciplines:

With regard to the types of disciplines studied, in the Indian higher education sector, most students at the under graduate level are enrolled in the arts stream (33.79%), followed by engineering & technology (18.89%) and commerce (14.51%). Whereas most students opt for management studies at the post graduate stage (20.64%), the leading stream at the M. Phil level is social science (24.07%). At the Ph. D. level, most students chose science in 2013 (22.15%).[21]

The NKC observed that in disciplines such as engineering, medicine and management there has been a rise in privatisation of education such that two-thirds to three-fourths of these seats are in private institutions. A UGC report in 2012 noted that the distribution of public and private institutions in India is skewed. This is because enrollment in public universities is largely concentrated in conventional disciplines (arts and sciences) whereas in private institutions, more students are enrolled in market-driven disciplines (engineering, management, etc).[22] A British Council report focusing on India, in 2014, suggested that the latter types of disciplines are typically more employable and that majority of firms hire engineering and management graduates.[23]

The Yashpal Committee also pointed out that while private investment is high in the emerging areas of engineering, medicine and management; majority of enrollment is still taking place in the traditional disciplines like arts, etc. The Committee said that the private sector should not confine itself to the commercially viable sectors such as management, accountancy, medicine, etc. Therefore, the responsibility of maximising enrollment currently stays with the government.

Reservations:

In the past, the Supreme Court has stated that private unaided educational institutions have full autonomy in their administration. The Court has also stated that the principle of merit should not be sacrificed, i.e., students should be admitted on the basis of their academic capability or merit. The management of a private institution can exercise its discretion for quota in admitting students, subject to satisfying the test of merit based admissions. This meant that the government could not mandate its reservation policy on a private unaided educational institute. Reservation is affirmative action for socially and economically backward classes, scheduled castes (SCs), scheduled tribes (STs), etc. The justification for disallowing reservations in these institutions was the encroachment of their right and autonomy in determining admission procedures, etc. Such reservation was only possible if decided mutually by the institution and the government.2,[24]

The Constitution (93rd Amendment) Act was enacted in 2005, inserting Article 15(5) in the Constitution. This empowered the government to mandate reservations in private (aided and unaided) educational institutions, except in minority educational institutions, for socially and educationally backward classes of citizens, SCs, STs, etc. This was challenged in 2008, wherein the Court upheld the constitutional validity of Article 15(5). It said that if reservations were imposed on these minority institutions, they would lose their minority character and would fail to be brought on the same platform as non-minorities. However, the Court left the question regarding applicability of reservations to private unaided institutions unanswered, as this aspect had not directly been challenged.[25] In 2014, this issue was challenged in Supreme Court in context of the Right to Education Act, 2010. The Act mandates 25% reservation in elementary schools (including private unaided) for economically weaker sections of society. The Court reasoned that the law mandates the government to reimburse the cost of such education to private institutes, and is in line with the constitutional goal of equality of opportunity. It held Article 15(5) constitutionally valid with regard to reservations in private unaided educational institutes.[26]

Fee structure:

Private higher education institutions are often accused of charging capitation fees (any amount in excess of fees charged for the course of study) from students, in turn making them unaffordable. Fee structures of private institutions may be one reason for inaccessibility of higher education. According to the Yashpal Committee figures in 2008, capitation fees in private institutions ranged from Rs 1-10 lakh for engineering courses, Rs 20-40 lakh for advanced courses in medicine, Rs 5-12 lakh for dental courses and Rs 30,000-50,000 for courses in arts and science.4

The Standing Committee on Human Resource Development, while examining the Prohibition of Unfair Practices in Technical Educational Institutions, Medical Educational Institutions and Universities Bill, 2010 (lapsed with the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha) stated that many private institutions charge exorbitant fees. In the absence of well-defined norms, fees charged by such universities have remained high.[27] UGC Regulations currently regulate fees for courses offered in deemed universities, to an extent. They state that the fees charged shall have a reasonable relation to the cost of running the course and the institution shall ensure that there is no commercialisation of education.13

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that the fees charged by private unaided educational institutes, could be regulated. Also, while banning capitation fee, it allowed institutes to charge a reasonable surplus.2 In 2003, the Court ruled that the fee structure in professional courses shall be approved by a committee in order to curb profiteering and charging of capitation fees. Post this judgment, some states such as Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka set up these committees. However, cases have been cited where some committees have determined the fee structure not by taking into account the financial viability of the institutes, but by how much students can afford to pay.1

Private institutions claim that certain other factors contribute to revision in fee structures: (i) sudden increase in charges, or levying of additional fee by the affiliating universities, sometimes requires the increase in fee structure, (ii) escalating maintenance of institutions, administrative expenses (maintenance of lab equipment, purchase of new software and so on) due to market variations and upward revision of pay for the staff, (iii) additional fees/charges in respect of value-added courses or services provided by the university, and (iv) other unforeseen circumstances.27

Quality

Accreditation:

It is important to improve the quality of higher education institutions along with quantitative expansion. Accreditation is a way of measuring such quality of institutions. It is the process of assessing the performance of institutions that volunteer to be accredited, on the basis of a few set parameters. These parameters may include: (i) curriculum, (ii) teaching-learning evaluation, (iii) research and consultancy, (iv) infrastructure and learning resources, (v) student support, (vi) governance, leadership and management, (vii) innovations and best practices, (viii) students’ performance, (ix) improvement in attainment of outcomes and, (x) facilities and technical support, etc. Once these have been considered a final grade is assigned to the institution by the accrediting authority.[28]

The objective behind such a review process is mainly to help potential students assess the quality of institutions and thereby make an informed choice. It also enables institutions to identify strengths, weaknesses and internal areas of planning. It may also be useful for providing data to funding agencies as well as enhancing employability of graduates.

In India, the National Assessment and Accreditation Council is an autonomous body established by UGC in 1994. Its main function is to ensure quality education via assessment and accreditation of institutions that volunteer for the same. The reassessment of an institution takes place after a period of five years. An institution may apply for reassessment of a grade it has been accredited with, by the Council, after one year of acquiring such a grade, but not later than three years.28 The National Board of Accreditation was established under the AICTE Act, 1987. The Board’s powers include: (i) conducting assessment or accreditation of a technical institution or programme, (ii) working with colleges and technical institutions to develop mechanisms for quality assessment, and (iii) sharing results of the assessment process with institutions. Largely, the Board looks at programme accreditation. Both the Council and the Board, accredit public and private higher education institutions.[29]

However, effective ways and strategies need to be devised to ensure that these bodies complete accreditation within the stipulated time frame. Currently, they suffer from a backlog of many applications of institutions waiting to be accredited (at the time of publishing their report in 2009, the NKC stated that only 10% of all institutions had been accredited). In addition, institutions need to ensure that post-accreditation complacency does not set in, as quality upgradation is not a one-time phenomenon. An Internal Quality Assurance Cell in institutions may continuously focus on academic excellence and administrative efficiency. Finally, accreditation bodies such as the Council may inform institutions, from time to time, where they stand in terms of standards of excellence from a global perspective.[30]

Table 2: International comparison of systems of accreditation

|

Country |

System of accreditation |

|

US |

Public and private agencies recognised by Federal Secretary of Education are allowed to accredit institutions or programmes. |

|

UK |

Both public and private bodies can be accrediting agencies. Universities receiving public funding or having degree giving powers are accredited by public bodies. Private institutions can be accredited by private bodies such as the British Accreditation Council and the Accreditation Service for International Colleges. |

|

Germany |

Accreditation agencies are private non-profit entities monitored by the Accreditation Council (under Foundation for the Accreditation of Study Programmes). |

|

Canada |

Membership to the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada is accepted as quality assurance. There are some province specific public or private accrediting agencies to accredit institutions. Some professional programmes (engineering and nursing) are also accredited by professional bodies. |

Sources: US Department of Higher Education; UK Border Office; Federation for Accreditation of Study Programmes Germany; Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada; PRS.

Annexure

State-wise number of private and public colleges, and enrollment

| State | No. of private colleges | No. of government colleges | % enrollment in private colleges | % enrollment in government colleges |

| Andaman & Nicobar Islands | 0 | 4 | 0 | 100% |

| Andhra Pradesh | 1423 | 139 | 91% | 9% |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 6 | 9 | 8% | 92% |

| Assam | 38 | 328 | 3% | 97% |

| Bihar | 81 | 452 | 14% | 86% |

| Chandigarh | 8 | 16 | 55% | 45% |

| Chhattisgarh | 336 | 294 | 46% | 54% |

| Dadra & Nagar Haveli | 4 | 2 | 53% | 47% |

| Daman & Diu | 4 | 2 | 20% | 80% |

| Delhi | 72 | 86 | 31% | 69% |

| Goa | 30 | 20 | 59% | 41% |

| Gujarat | 1345 | 476 | 70% | 30% |

| Haryana | 531 | 149 | 64% | 36% |

| Himachal Pradesh | 132 | 122 | 36% | 64% |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 112 | 107 | 16% | 84% |

| Jharkhand | 60 | 115 | 15% | 85% |

| Karnataka | 2442 | 604 | 71% | 29% |

| Kerala | 645 | 151 | 84% | 16% |

| Madhya Pradesh | 1200 | 555 | 52% | 48% |

| Maharashtra | 3522 | 769 | 78% | 22% |

| Manipur | 34 | 48 | 43% | 57% |

| Meghalaya | 23 | 14 | 63% | 37% |

| Mizoram | 1 | 28 | 1% | 99% |

| Nagaland | 39 | 21 | 64% | 36% |

| Odisha | 553 | 286 | 63% | 37% |

| Puducherry | 48 | 24 | 62% | 38% |

| Punjab | 330 | 105 | 63% | 37% |

| Rajasthan | 840 | 283 | 41% | 59% |

| Sikkim | 5 | 7 | 14% | 86% |

| Tamil Nadu | 2141 | 335 | 83% | 17% |

| Telangana | 1242 | 143 | 87% | 13% |

| Tripura | 6 | 39 | 6% | 94% |

| Uttar Pradesh | 2460 | 544 | 85% | 15% |

| Uttarakhand | 136 | 95 | 35% | 65% |

| West Bengal | 541 | 396 | 36% | 64% |

| All India | 20390 | 6768 | 64% | 36% |

Sources: AISHE 2014; PRS.

*Note: Figures based on actual responses received by Ministry during survey.

[1] Islamic Academy of Education vs. State of Karnataka & Ors., Writ Petition (Civil) 350 of 1993.

[2] TMA Pai Foundation vs. State of Karnataka &Ors., Write Petition (Civil) 317 of 1993.

[3] “Report to the Nation: 2006-2009”, National Knowledge Commission, March 2009, http://www.aicte-india.org/downloads/nkc.pdf.

[4] “ Report of the Committee to Advise on Renovation and Rejuvenation of Higher Education”, 2009, http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/document-reports/YPC-Report.pdf.

[5] Entry 25, Concurrent List, Constitution of India.

[6] Entry 66, Union List, Constitution of India.

[7] Entry 32, State List, Constitution of India.

[8] “Report of the Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE) Committee on Autonomy of Higher Education Institutions”, Ministry of Human Resource Development, June 2005, http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/document-reports/AutonomyHEI.pdf.

[9] Entry 64, Union List, Constitution of India.

[10] Unstarred Question No. 1628, Lok Sabha, December 3, 2014.

[11] “All India Survey on Higher Education 2013-14 (Provisional)”, Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2015, http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/statistics/AISHE13-14P.pdf.

[12] Rajasthan Private Universities Act, 2005, May 8, 2005, http://www.lawsofindia.org/pdf/rajasthan/2005/2005Rajasthan10.pdf; Madhya Pradesh Niji Vishwavidyalaya (Sthapana Avam Sanchalan) Adhiniyam, 2007, May 25, 2007, http://www.highereducation.mp.gov.in/adhiniyam/PrivateUniversityACt2007English.pdf; Gujarat Private Universities Act, 2009, July 7, 2009, http://gujarat-education.gov.in/education/Images/extra-9.pdf.

[13] “UGC (Institutions Deemed to be Universities) Regulations, 2010”, University Grants Commission, May 21, 2010, http://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/regulations/gazzeetenglish.pdf; UGC (Institutions Deemed to be Universities) (Amendment) Regulations, 2014, http://www.ugc.ac.in/pdfnews/1842250_deemedregulation2014.PDF.

[14] Viplav Sharma vs. Union of India & Ors., Writ Petition (Civil) 142 of 2006.

[15] University Grants Commission Act, 1956, Ministry of Human Resource Development.

[16] All India Council for Technical Education Act, 1987, Ministry of Human Resource Development.

[17] Single year age data, Population Enumeration Data (Final Population), 2011 Census of India.

[18] “265th Report: Demands for Grants 2015-16 (Demand No. 60) of the Department of Higher Education”, Standing Committee on Human Resource Development, April 23, 2015, http://164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/EnglishCommittees/Committee%20on%20HRD/265.pdf.

[19] Demands for Grants of Department of Higher Education, Expenditure Budget, http://indiabudget.nic.in/index.asp.

[20] “Education at a Glance 2010”, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Indicators, 2010, http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/45926093.pdf.

[21] “All India Survey on Higher Education 2012-13 (Provisional)”, Ministry of Human Resource Development, 2015, http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/statistics/AISHE2012-13F.pdf.

[22] “Inclusive and Qualitative Expansion of Higher Education 2012-17”, University Grants Commission, November 2011, http://www.ugc.ac.in/ugcpdf/740315_12FYP.pdf.

[23] “India Employability Survey Report 2014”, British Council, 2014, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/campuslife/services/careers/Students-Graduates/Global-Careers/India-Employability-Report-2014--FINAL.pdf.

[24] P.A. Inamdar and Ors. vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors., Appeal (Civil) 5041 of 2005.

[25] Ashoka Kumar Thakur vs. Union of India & Ors., Writ Petition (Civil) 265 of 2006.

[26] Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust & Ors. vs. Union of India & Ors., Writ Petition (Civil) 416 of 2012.

[27] “236th Report on the Prohibition of Unfair Practices in Technical Educational Institutions, Medical Educational Institutions and Universities Bill, 2010”, Standing Committee on Human Resource Development, May 30, 2011, http://164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/EnglishCommittees/Committee%20on%20HRD/236.pdf.

[28] National Assessment and Accreditation Council of India, University Grants Commission, http://www.naac.gov.in/.

[29] National Board of Accreditation, All India Council for Technical Education, http://www.nbaind.org/views/Home.aspx.

[30] “Higher Education in India: Issues, Concerns and New Directions”, University Grants Commission, December 2003, http://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/pub/he/heindia.pdf.

DISCLAIMER: This document is being furnished to you for your information. You may choose to reproduce or redistribute this report for non-commercial purposes in part or in full to any other person with due acknowledgement of PRS Legislative Research (“PRS”). The opinions expressed herein are entirely those of the author(s). PRS makes every effort to use reliable and comprehensive information, but PRS does not represent that the contents of the report are accurate or complete. PRS is an independent, not-for-profit group. This document has been prepared without regard to the objectives or opinions of those who may receive it.