A few weeks ago, in response to the initial protests by farmers against the new central farm laws, three state assemblies – Chhattisgarh, Punjab, and Rajasthan – passed Bills to address farmers’ concerns. While these Bills await the respective Governors’ assent, protests against the central farm laws have gained momentum. In this blog, we discuss the key amendments proposed by these states in response to the central farm laws.

What are the central farm laws and what do they seek to do?

In September 2020, Parliament enacted three laws: (i) the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, (ii) the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, and (iii) the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020. The laws collectively seek to: (i) facilitate barrier-free trade of farmers’ produce outside the markets notified under the various state Agriculture Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) laws, (ii) define a framework for contract farming, and (iii) regulate the supply of certain food items, including cereals, pulses, potatoes, and onions, only under extraordinary circumstances such as war, famine, and extraordinary price rise.

How do the central farm laws change the agricultural regulatory framework?

Agricultural marketing in most states is regulated by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs), set up under the state APMC Act. The central farm laws seek to facilitate multiple channels of marketing outside the existing APMC markets. Many of these existing markets face issues such as limited number of buyers restricting the entry of new players and undue deductions in the form of commission charges and market fees. The central laws introduced a liberalised agricultural marketing system with the aim of increasing the availability of buyers for farmers’ produce. More buyers would lead to competition in the agriculture market resulting in better prices for farmers.

Why have states proposed amendments to the central farm laws?

The central farm laws allow anyone with a PAN card to buy farmers’ produce in the ‘trade area’ outside the markets notified or run by the APMCs. Buyers do not need to get a license from the state government or APMC, or pay any tax to them for such purchase in the ‘trade area’. These changes in regulations raised concerns regarding the kind of protections available to farmers in the ‘trade area’ outside APMC markets, particularly in terms of the price discovery and payment. To address such concerns, the states of Chhattisgarh, Punjab, and Rajasthan, in varying forms, proposed amendments to the existing agricultural marketing laws.

The Punjab and Rajasthan assemblies passed Bills to amend the central Acts, in their application to these states. The Chhattisgarh Assembly passed a Bill to amend its APMC Act in response to the central Acts. These state Bills aim to prevent exploitation of farmers and ensure an optimum guarantee of fair market price for the agriculture produce. Among other things, these state Bills enable state governments to levy market fee outside the physical premises of the state APMC markets, mandate MSP for certain types of agricultural trade, and enable state governments to regulate the production, supply, and distribution of essential commodities and impose stock limits under extraordinary circumstances.

Chhattisgarh

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 allows anyone with a PAN card to buy farmers’ produce in the trade area outside the markets notified or run by the APMCs. Buyers do not need to get a license from the state government or APMC, or pay any tax to them for such purchase in the trade area. The Chhattisgarh Assembly passed a Bill to amend its APMC Act to allow the state government to notify structures outside APMC markets, such as godowns, cold storages, and e-trading platforms, as deemed markets. This implies that such deemed markets will be under the jurisdiction of the APMCs as per the central Act. Thus, APMCs in Chhattisgarh can levy market fee on sale of farmers’ produce in such deemed markets (outside the APMC markets) and require the buyer to have a license.

Punjab and Rajasthan

The Punjab and Rajasthan Bills empower the respective state governments to levy a market fee (on private traders, and electronic trading platforms) for trade outside the state APMC markets. Further, they mandate that in certain cases, agricultural produce should not be sold or purchased at a price below the Minimum Support Price (MSP). For instance, in Punjab sale and purchase of wheat and paddy should not be below MSP. The Bills also provide that they will override any other law currently in force. Table 1 gives a comparison of the amendments proposed by states with the related provisions of the central farm laws.

Table 1: Comparison of the central farm laws with amendments proposed by Punjab and Rajasthan

|

Provision |

Central laws |

State amendments |

|

Market fee |

|

|

|

Minimum Support Price (MSP) - fixed by the central government, based on the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices |

|

|

|

Penalties for compeling farmers to sell below MSP |

|

|

|

Delivery under farming agreements |

|

|

|

Regulation of essential commodities |

|

|

|

Imposition of stock limit |

|

|

|

Dispute Resolution Mechanism for Farmers |

|

|

|

Power of civil courts |

|

|

|

Special provisions |

|

|

Note: A market committee provides facilities for and regulates the marketing of agricultural produce in a designated market area.

Have the state amendments come into force?

The amendments proposed by states aim to address the concerns of farmers, but to a varying extent. The Bills have not come into force yet as they await the Governors’ assent. In addition, the Punjab and Rajasthan Bills also need the assent of the President, as they are inconsistent with the central Acts and seek to amend them. Meanwhile, amidst the ongoing protests, many farmers’ organisations are in talks with the central government to seek redressal of their grievances and appropriate changes in the central farm laws. It remains to be seen to what extent will such changes address the concerns of farmers.

A version of this article first appeared on Firstpost on December 5, 2020.

The central government has enforced a nation-wide lockdown between March 25 and May 3 as part of its measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. During the lockdown, several restrictions have been placed on the movement of individuals and economic activities have come to a halt barring the activities related to essential goods and services. The restrictions are being relaxed in less affected areas in a limited manner since April 20. In this blog, we look at how the lockdown has impacted the demand and supply of electricity and what possible repercussions its prolonged effect may have on the power sector.

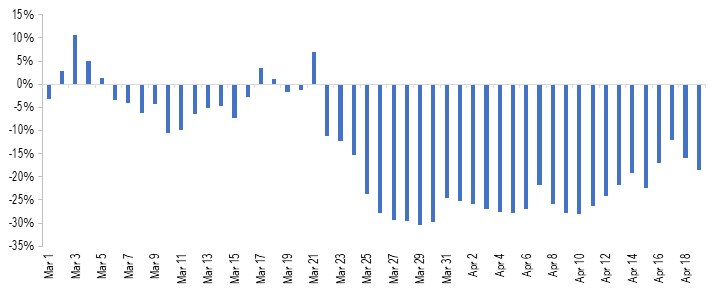

Power supply saw a decrease of 25% during the lockdown (year-on-year)

As electricity cannot be stored in large amount, the power generation and supply for a given day are planned based on the forecast for demand. The months of January and February in 2020 had seen an increase of 3% and 7% in power supply, respectively as compared to 2019 (year-on-year). In comparison, the power supply saw a decrease of 3% between March 1 and March 24. During the lockdown between March 24 and April 19, the total power supply saw a decrease of about 25% (year-on-year).

Figure 1: % change in power supply position between March 1 and April 19 (Y-o-Y from 2019 to 2020)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

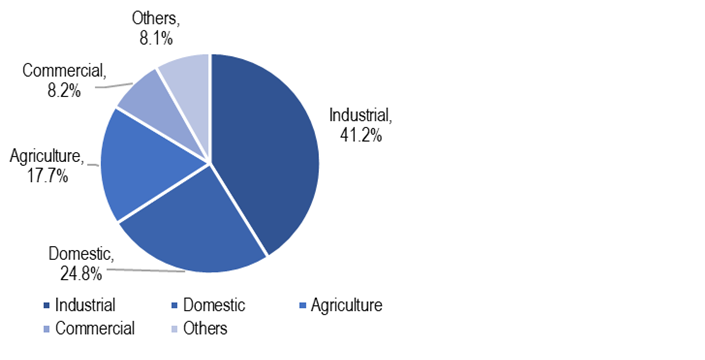

If we look at the consumption pattern by consumer category, in 2018-19, 41% of total electricity consumption was for industrial purposes, followed by 25% for domestic and 18% for agricultural purposes. As the lockdown has severely reduced the industrial and commercial activities in the country, these segments would have seen a considerable decline in demand for electricity. However, note that the domestic demand may have seen an uptick as people are staying indoors.

Figure 2: Power consumption by consumer segment in 2018-19

Sources: Central Electricity Authority; PRS.

Electricity demand may continue to be subdued over the next few months. At this point, it is unclear that when lockdown restrictions are eased, how soon will economic activities return to pre COVID-19 levels. India’s growth projections also highlight a slowdown in the economy in 2020 which will further impact the demand for electricity. On April 16, the International Monetary Fund has slashed its projection for India’s GDP growth in 2020 from 5.8% to 1.9%.

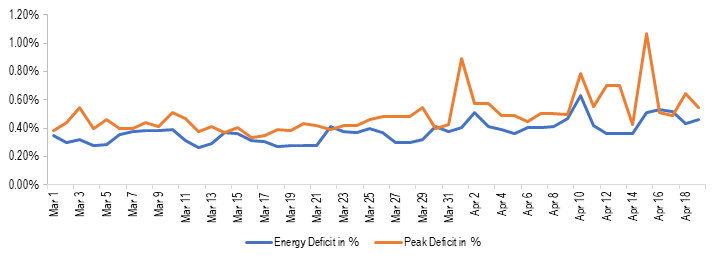

A nominal increase in energy and peak deficit levels

As power sector related operations have been classified as essential services, the plant operations and availability of fuel (primarily coal) have not been significantly constrained. This can be observed with the energy deficit and peak deficit levels during the lockdown period which have remained at a nominal level. Energy deficit indicates the shortfall in energy supply against the demand during the day. The average energy deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.42% while the corresponding figure was 0.33% between March 1 and March 24. Similarly, the average peak deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.56% as compared to 0.41% between March 1 and March 24. Peak deficit indicates the shortfall in supply against demand during highest consumption period in a day.

Figure 3: Energy deficit and peak deficit between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in %)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Coal stock with power plants increases

Coal is the primary source of power generation in the country (~71% in March 2020). During the lockdown period, the coal stock with coal power plants has seen an increase. As of April 19, total coal-stock with the power plants in the country (in days) has risen to 29 days as compared to 24 days on March 24. This indicates that the supply of coal has not been constrained during the lockdown, at least to the extent of meeting the requirements of power plants.

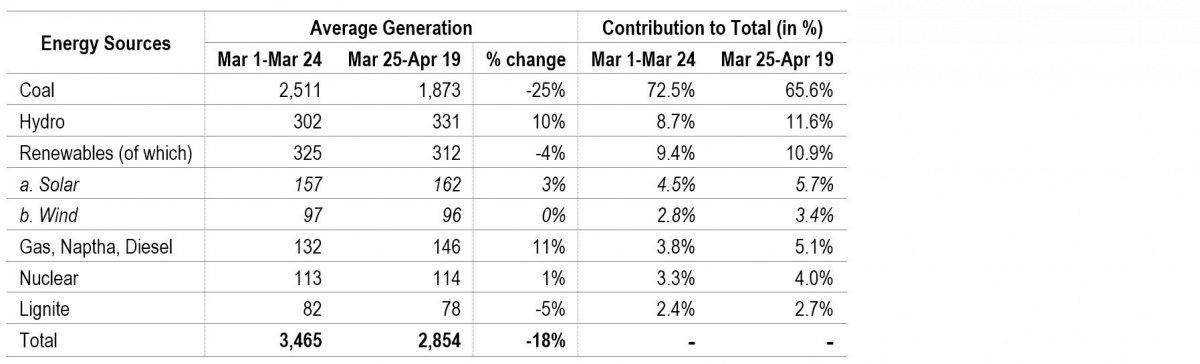

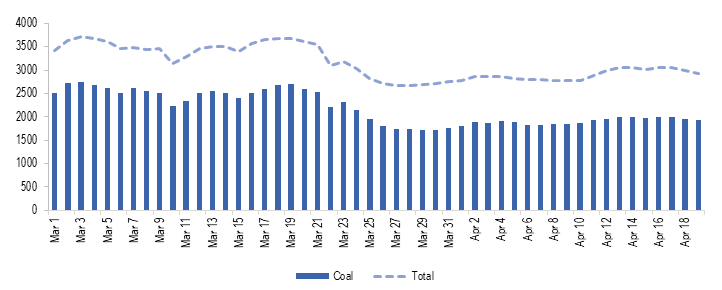

Energy mix changes during the lockdown, power generation from coal impacted

During the lockdown, power generation has been adjusted to compensate for reduced consumption, Most of this reduction in consumption has been adjusted by reduced coal power generation. As can be seen in Table 1, coal power generation reduced from an average of 2,511 MU between March 1 and March 24 to 1,873 MU between March 25 and April 19 (about 25%). As a result, the contribution of coal in total power generation reduced from an average of 72.5% to 65.6% between these two periods.

Table 1: Energy Mix during March 1-April 19, 2020

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

This shift may be happening due to various reasons including: (i) renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and small hydro) have MUST RUN status, i.e., the power generated by them has to be given the highest priority by distribution companies, and (ii) running cost of renewable power plants is lower as compared to thermal power plants.

This suggests that if growth in electricity demand were to remain weak, the adverse impact on the coal power plants could be more as compared to other power generation sources. This will also translate into weak demand for coal in the country as almost 87% of the domestic coal production is used by the power sector. Note that the plant load factor (PLF) of the thermal power plants has seen a considerable decline over the years, decreasing from 77.5% in 2009-10 to 56.4% in 2019-20. Low PLF implies that coal plants have been lying idle. Coal power plants require significant fixed costs, and they incur such costs even when the plant is lying idle. The declining capacity utilisation augmented by a weaker demand will undermine the financial viability of these plants further.

Figure 4: Power generation from coal between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in MU)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Finances of the power sector to be severely impacted

Power distribution companies (discoms) buy power from generation companies and supply it to consumers. In India, most of the discoms are state-owned utilities. One of the key concerns in the Indian power sector has been the poor financial health of its discoms. The discoms have had high levels of debt and have been running losses. The debt problem was partly addressed under the UDAY scheme as state governments took over 75% of the debt of state-run discoms (around 2.1 lakh crore in two years 2015-16 and 2016-17). However, discoms have continued to register losses owing to underpricing of electricity tariff for some consumer segments, and other forms of technical and commercial losses. Outstanding dues of discoms towards power generation companies have also been increasing, indicating financial stress in some discoms. At the end of February 2020, the total outstanding dues of discoms to generation companies stood at Rs 92,602 crore.

Due to the lockdown and its further impact in the near term, the financial situation of discoms is likely to be aggravated. This will also impact other entities in the value chain including generation companies and their fuel suppliers. This may lead to reduced availability of working capital for these entities and an increase in the risk of NPAs in the sector. Note that, as of February 2020, the power sector has the largest share in the deployment of domestic bank credit among industries (Rs 5.4 lakh crore, 19.3% of total).

Following are some of the factors which have impacted the financial situation during the lockdown:

Reduced cross-subsidy: In most states, the electricity tariff for domestic and agriculture consumers is lower than the actual cost of supply. Along with the subsidy by the state governments, this gap in revenue is partly compensated by charging industrial and commercial consumers at a higher rate. Hence, industrial and commercial segments cross-subsidise the power consumption by domestic and agricultural consumers.

The lockdown has led to a halt on commercial and industrial activities while people are staying indoors. This has led to a situation where the demand from the consumer segments who cross-subsidise has decreased while the demand from consumer segments who are cross-subsidised has increased. Due to this, the gap between revenue realised by discoms and cost of supply will widen, leading to further losses for discoms. States may choose to bridge this gap by providing a higher subsidy.

Moratorium to consumers: To mitigate the financial hardship of citizens due to COVID-19, some states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Goa, among others, have provided consumers with a moratorium for payment of electricity bills. At the same time, the discoms are required to continue supplying electricity. This will mean that the return for the supply made in March and April will be delayed, leading to lesser cash in hand for discoms.

Some state governments such as Bihar also announced a reduction in tariff for domestic and agricultural consumers. Although, the reduction in tariff will be compensated to discoms by government subsidy.

Constraints with government finances: The revenue collection of states has been severely impacted as economic activities have come to a halt. Further, the state governments are directing their resources for funding relief measures such as food distribution, direct cash transfers, and healthcare. This may adversely affect or delay the subsidy transfer to discoms.

The UDAY scheme also requires states to progressively fund greater share in losses of discoms from their budgetary resources (10% in 2018-19, 25% in 2019-20, and 50% in 2020-21). As losses of discoms may widen due to the above-mentioned factors, the state government’s financial burden is likely to increase.

Capacity addition may be adversely impacted

As per the National Electricity Plan, India’s total capacity addition target is around 176 GW for 2017-2022. This comprises of 118 GW from renewable sources, 6.8 GW from hydro sources, and 6.4 GW from coal (apart from 47.8 GW of coal-based power projects already in various stages of production as of January 2018).

India has set a goal of installing 175 GW of Renewable Power Capacity by 2022 as part of its climate change commitments (86 GW has been installed as of January 2020). In January 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy observed that India could only install 82% and 55% of its annual renewable energy capacity addition targets in 2017-18 and 2018-19. As of January 2020, 67% of the target has been achieved for 2019-20.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, the capacity addition targets for various sources is likely to be adversely impacted in the short run as:

construction activities were stopped during the lockdown and will take some time to return to normal,

disruption in the global supply chain may lead to difficulties with the availability of key components leading to delay in execution of projects, for instance, for solar power plants, solar PV modules are mainly imported from China, and

reduced revenue for companies due to weak demand will leave companies with less capacity left for capital expenditure.

Key reforms likely to be delayed

Following are some of the important reforms anticipated in 2020-21 which may get delayed due to the developing situation:

The real-time market for electricity: The real-time market for electricity was to be operationalised from April 1, 2020. However, the lockdown has led to delay in completion of testing and trial runs. The revised date for implementation is now June 1, 2020.

UDAY 2.0/ADITYA: A new scheme for the financial turnaround of discoms was likely to come this year. The scheme would have provided for the installation of smart meters and incentives for rationalisation of the tariff, among other things. It remains to be seen what this scheme would be like since the situation with government finances is also going to worsen due to anticipated economic slowdown.

Auction of coal blocks for commercial mining: The Coal Ministry has been considering auction of coal mines for commercial mining this year. 100% FDI has been allowed in the coal mining activity for commercial sale of coal to attract foreign players. However, the global economic slowdown may mean that the auctions may not generate enough interest from foreign as well as domestic players.

For a detailed analysis of the Indian Power Sector, please see here. For details on the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the country and across states, please see here. For details on the major COVID-19 related notifications released by the centre and the states, please see here.