Applications for the LAMP Fellowship 2026-27 are closed. Shortlisted candidates will be asked to take an online test on January 4, 2026.

The central government has enforced a nation-wide lockdown between March 25 and May 3 as part of its measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. During the lockdown, several restrictions have been placed on the movement of individuals and economic activities have come to a halt barring the activities related to essential goods and services. The restrictions are being relaxed in less affected areas in a limited manner since April 20. In this blog, we look at how the lockdown has impacted the demand and supply of electricity and what possible repercussions its prolonged effect may have on the power sector.

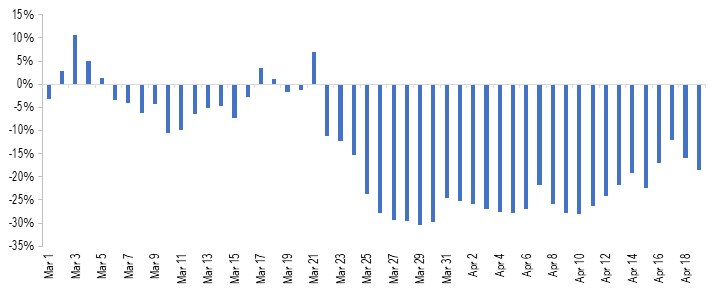

Power supply saw a decrease of 25% during the lockdown (year-on-year)

As electricity cannot be stored in large amount, the power generation and supply for a given day are planned based on the forecast for demand. The months of January and February in 2020 had seen an increase of 3% and 7% in power supply, respectively as compared to 2019 (year-on-year). In comparison, the power supply saw a decrease of 3% between March 1 and March 24. During the lockdown between March 24 and April 19, the total power supply saw a decrease of about 25% (year-on-year).

Figure 1: % change in power supply position between March 1 and April 19 (Y-o-Y from 2019 to 2020)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

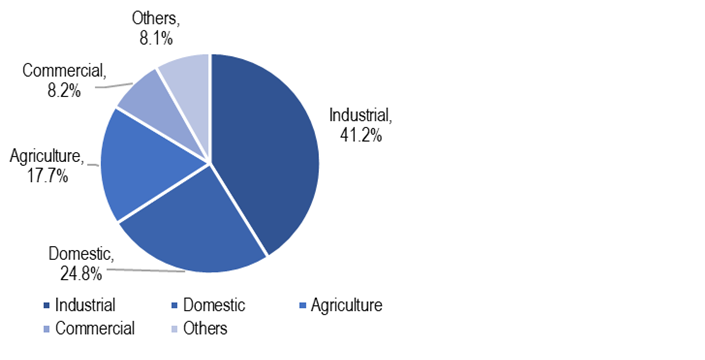

If we look at the consumption pattern by consumer category, in 2018-19, 41% of total electricity consumption was for industrial purposes, followed by 25% for domestic and 18% for agricultural purposes. As the lockdown has severely reduced the industrial and commercial activities in the country, these segments would have seen a considerable decline in demand for electricity. However, note that the domestic demand may have seen an uptick as people are staying indoors.

Figure 2: Power consumption by consumer segment in 2018-19

Sources: Central Electricity Authority; PRS.

Electricity demand may continue to be subdued over the next few months. At this point, it is unclear that when lockdown restrictions are eased, how soon will economic activities return to pre COVID-19 levels. India’s growth projections also highlight a slowdown in the economy in 2020 which will further impact the demand for electricity. On April 16, the International Monetary Fund has slashed its projection for India’s GDP growth in 2020 from 5.8% to 1.9%.

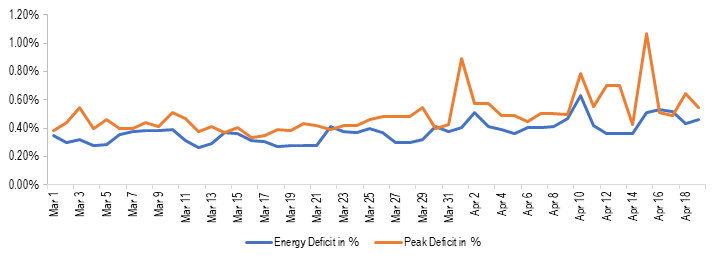

A nominal increase in energy and peak deficit levels

As power sector related operations have been classified as essential services, the plant operations and availability of fuel (primarily coal) have not been significantly constrained. This can be observed with the energy deficit and peak deficit levels during the lockdown period which have remained at a nominal level. Energy deficit indicates the shortfall in energy supply against the demand during the day. The average energy deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.42% while the corresponding figure was 0.33% between March 1 and March 24. Similarly, the average peak deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.56% as compared to 0.41% between March 1 and March 24. Peak deficit indicates the shortfall in supply against demand during highest consumption period in a day.

Figure 3: Energy deficit and peak deficit between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in %)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Coal stock with power plants increases

Coal is the primary source of power generation in the country (~71% in March 2020). During the lockdown period, the coal stock with coal power plants has seen an increase. As of April 19, total coal-stock with the power plants in the country (in days) has risen to 29 days as compared to 24 days on March 24. This indicates that the supply of coal has not been constrained during the lockdown, at least to the extent of meeting the requirements of power plants.

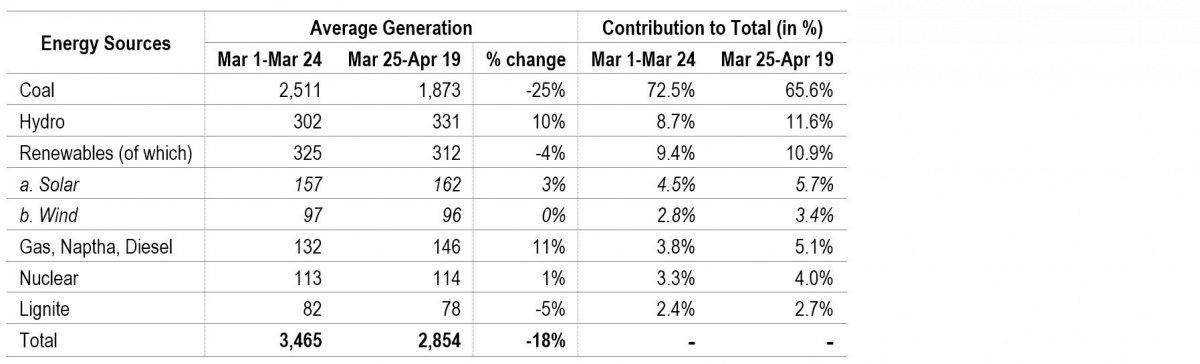

Energy mix changes during the lockdown, power generation from coal impacted

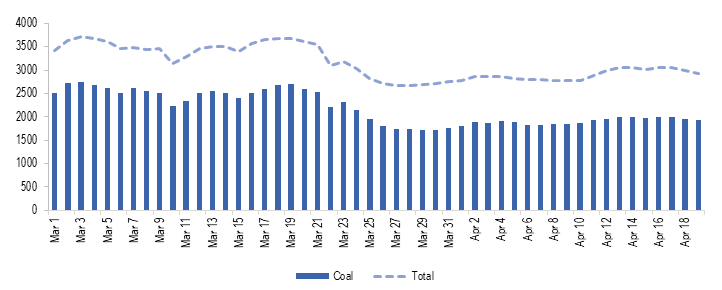

During the lockdown, power generation has been adjusted to compensate for reduced consumption, Most of this reduction in consumption has been adjusted by reduced coal power generation. As can be seen in Table 1, coal power generation reduced from an average of 2,511 MU between March 1 and March 24 to 1,873 MU between March 25 and April 19 (about 25%). As a result, the contribution of coal in total power generation reduced from an average of 72.5% to 65.6% between these two periods.

Table 1: Energy Mix during March 1-April 19, 2020

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

This shift may be happening due to various reasons including: (i) renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and small hydro) have MUST RUN status, i.e., the power generated by them has to be given the highest priority by distribution companies, and (ii) running cost of renewable power plants is lower as compared to thermal power plants.

This suggests that if growth in electricity demand were to remain weak, the adverse impact on the coal power plants could be more as compared to other power generation sources. This will also translate into weak demand for coal in the country as almost 87% of the domestic coal production is used by the power sector. Note that the plant load factor (PLF) of the thermal power plants has seen a considerable decline over the years, decreasing from 77.5% in 2009-10 to 56.4% in 2019-20. Low PLF implies that coal plants have been lying idle. Coal power plants require significant fixed costs, and they incur such costs even when the plant is lying idle. The declining capacity utilisation augmented by a weaker demand will undermine the financial viability of these plants further.

Figure 4: Power generation from coal between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in MU)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Finances of the power sector to be severely impacted

Power distribution companies (discoms) buy power from generation companies and supply it to consumers. In India, most of the discoms are state-owned utilities. One of the key concerns in the Indian power sector has been the poor financial health of its discoms. The discoms have had high levels of debt and have been running losses. The debt problem was partly addressed under the UDAY scheme as state governments took over 75% of the debt of state-run discoms (around 2.1 lakh crore in two years 2015-16 and 2016-17). However, discoms have continued to register losses owing to underpricing of electricity tariff for some consumer segments, and other forms of technical and commercial losses. Outstanding dues of discoms towards power generation companies have also been increasing, indicating financial stress in some discoms. At the end of February 2020, the total outstanding dues of discoms to generation companies stood at Rs 92,602 crore.

Due to the lockdown and its further impact in the near term, the financial situation of discoms is likely to be aggravated. This will also impact other entities in the value chain including generation companies and their fuel suppliers. This may lead to reduced availability of working capital for these entities and an increase in the risk of NPAs in the sector. Note that, as of February 2020, the power sector has the largest share in the deployment of domestic bank credit among industries (Rs 5.4 lakh crore, 19.3% of total).

Following are some of the factors which have impacted the financial situation during the lockdown:

Reduced cross-subsidy: In most states, the electricity tariff for domestic and agriculture consumers is lower than the actual cost of supply. Along with the subsidy by the state governments, this gap in revenue is partly compensated by charging industrial and commercial consumers at a higher rate. Hence, industrial and commercial segments cross-subsidise the power consumption by domestic and agricultural consumers.

The lockdown has led to a halt on commercial and industrial activities while people are staying indoors. This has led to a situation where the demand from the consumer segments who cross-subsidise has decreased while the demand from consumer segments who are cross-subsidised has increased. Due to this, the gap between revenue realised by discoms and cost of supply will widen, leading to further losses for discoms. States may choose to bridge this gap by providing a higher subsidy.

Moratorium to consumers: To mitigate the financial hardship of citizens due to COVID-19, some states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Goa, among others, have provided consumers with a moratorium for payment of electricity bills. At the same time, the discoms are required to continue supplying electricity. This will mean that the return for the supply made in March and April will be delayed, leading to lesser cash in hand for discoms.

Some state governments such as Bihar also announced a reduction in tariff for domestic and agricultural consumers. Although, the reduction in tariff will be compensated to discoms by government subsidy.

Constraints with government finances: The revenue collection of states has been severely impacted as economic activities have come to a halt. Further, the state governments are directing their resources for funding relief measures such as food distribution, direct cash transfers, and healthcare. This may adversely affect or delay the subsidy transfer to discoms.

The UDAY scheme also requires states to progressively fund greater share in losses of discoms from their budgetary resources (10% in 2018-19, 25% in 2019-20, and 50% in 2020-21). As losses of discoms may widen due to the above-mentioned factors, the state government’s financial burden is likely to increase.

Capacity addition may be adversely impacted

As per the National Electricity Plan, India’s total capacity addition target is around 176 GW for 2017-2022. This comprises of 118 GW from renewable sources, 6.8 GW from hydro sources, and 6.4 GW from coal (apart from 47.8 GW of coal-based power projects already in various stages of production as of January 2018).

India has set a goal of installing 175 GW of Renewable Power Capacity by 2022 as part of its climate change commitments (86 GW has been installed as of January 2020). In January 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy observed that India could only install 82% and 55% of its annual renewable energy capacity addition targets in 2017-18 and 2018-19. As of January 2020, 67% of the target has been achieved for 2019-20.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, the capacity addition targets for various sources is likely to be adversely impacted in the short run as:

construction activities were stopped during the lockdown and will take some time to return to normal,

disruption in the global supply chain may lead to difficulties with the availability of key components leading to delay in execution of projects, for instance, for solar power plants, solar PV modules are mainly imported from China, and

reduced revenue for companies due to weak demand will leave companies with less capacity left for capital expenditure.

Key reforms likely to be delayed

Following are some of the important reforms anticipated in 2020-21 which may get delayed due to the developing situation:

The real-time market for electricity: The real-time market for electricity was to be operationalised from April 1, 2020. However, the lockdown has led to delay in completion of testing and trial runs. The revised date for implementation is now June 1, 2020.

UDAY 2.0/ADITYA: A new scheme for the financial turnaround of discoms was likely to come this year. The scheme would have provided for the installation of smart meters and incentives for rationalisation of the tariff, among other things. It remains to be seen what this scheme would be like since the situation with government finances is also going to worsen due to anticipated economic slowdown.

Auction of coal blocks for commercial mining: The Coal Ministry has been considering auction of coal mines for commercial mining this year. 100% FDI has been allowed in the coal mining activity for commercial sale of coal to attract foreign players. However, the global economic slowdown may mean that the auctions may not generate enough interest from foreign as well as domestic players.

For a detailed analysis of the Indian Power Sector, please see here. For details on the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the country and across states, please see here. For details on the major COVID-19 related notifications released by the centre and the states, please see here.

Compulsory voting at elections to local bodies in Gujarat Last week, the Gujarat Local Authorities Laws (Amendment) Act, 2009 received the Governor’s assent. The Act introduces an ‘obligation to vote’ at the municipal corporation, municipality and Panchayat levels in the state of Gujarat. To this end, the Act amends three laws related to administration at the local bodies- the Bombay Provincial Municipal Corporation Act, 1949; the Gujarat Municipalities Act, 1963 and; the Gujarat Panchayats Act, 1993. Following the amendments, it shall now be the duty of a qualified voter to cast his vote at elections to each of these bodies. This includes the right to exercise the NOTA option. The Act empowers an election officer to serve a voter notice on the grounds that he appears to have failed to vote at the election. The voter is then required to provide sufficient reasons within a period of one month, failing which he is declared as a “defaulter voter” by an order. The defaulter voter has the option of challenging this order before a designated appellate officer, whose decision will be final. At this stage, it is unclear what the consequences for being a default voter may be, as the penalties for the same are to be prescribed in the Rules. Typically, any disadvantage or penalty to be suffered by an individual for violating a provision of law is prescribed in the parent act itself, and not left to delegated legislation. The Act carves out exemptions for certain individuals from voting if (i) he is rendered physically incapable due to illness etc.; (ii) he is not present in the state of Gujarat on the date of election; or (iii) for any other reasons to be laid down in the Rules. The previous Governor had withheld her assent on the Bill for several reasons. The Governor had stated that compulsory voting violated Article 21 of the Constitution and the principles of individual liberty that permits an individual not to vote. She had also pointed out that the Bill was silent on the government’s duty to create an enabling environment for the voter to cast his vote. This included updating of electoral rolls, timely distribution of voter ID cards to all individuals and ensuring easy access to polling stations. Right to vote in India Many democratic governments consider participating in national elections a right of citizenship. In India, the right to vote is provided by the Constitution and the Representation of People’s Act, 1951, subject to certain disqualifications. Article 326 of the Constitution guarantees the right to vote to every citizen above the age of 18. Further, Section 62 of the Representation of Peoples Act (RoPA), 1951 states that every person who is in the electoral roll of that constituency will be entitled to vote. Thus, the Constitution and the RoPA make it clear that every individual above the age of 18, whose name is in the electoral rolls, and does not attract any of the disqualifications under the Act, may cast his vote. This is a non discriminatory, voluntary system of voting. In1951, during the discussion on the People’s Representation Bill in Parliament, the idea of including compulsory voting was mooted by a Member. However, it was rejected by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar on account of practical difficulties. Over the decades, of the various committees that have discussed electoral reforms, the Dinesh Goswami Committee (1990) briefly examined the issue of compulsory voting. One of the members of the committee had suggested that the only effective remedy for low voter turn outs was introducing the system of compulsory voting. This idea was rejected on the grounds that there were practical difficulties involved in its implementation. In July 2004, the Compulsory Voting Bill, 2004 was introduced as a Private Member Bill by Mr. Bachi Singh Rawat, a Member of Parliament in the Lok Sabha. The Bill proposed to make it compulsory for every eligible voter to vote and provided for exemption only in certain cases, like that of illness etc. Arguments mooted against the Bill included that of remoteness of polling booths, difficulties faced by certain classes of people like daily wage labourers, nomadic groups, disabled, pregnant women etc. in casting their vote. The Bill did not receive the support of the House and was not passed. Another Private Member Bill related to Compulsory Voting was introduced by Mr. JP Agarwal, Member of Parliament, in 2009. Besides making voting mandatory, this Bill also cast the duty upon the state to ensure large number of polling booths at convenient places, and special arrangements for senior citizens, persons with physical disability and pregnant women. The then Law Minister, Mr. Moily argued that if compulsory voting was introduced, Parliament would reflect, more accurately, the will of the electorate. However, he also stated that active participation in a democratic set up must be voluntary, and not coerced. Compulsory voting in other countries A number of countries around the world make it mandatory for citizens to vote. For example, Australia mandates compulsory voting at the national level. The penalty for violation includes an explanation for not voting and a fine. It may be noted that the voter turnout in Australia has usually been above 90%, since 1924. Several countries in South America including Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia also have a provision for compulsory voting. Certain other countries like The Netherlands in 1970 and Austria more recently, repealed such legal requirements after they had been in force for decades. Other democracies like the UK, USA, Germany, Italy and France have a system of voluntary voting. Typically, over the last few elections, Italy has had a voter turnout of over 80%, while the USA has a voter turnout of about 50%. What compulsory voting would mean Those in favour of compulsory voting assert that a high turnout is important for a proper democratic mandate and the functioning of democracy. They also argue that people who know they will have to vote will take politics more seriously and start to take a more active role. Further, citizens who live in a democratic state have a duty to vote, which is an essential part of that democracy. However, some others have argued that compulsory voting may be in violation of the fundamental rights of liberty and expression that are guaranteed to citizens in a democratic state. In this context, it has been stated that every individual should be able to choose whether or not he or she wants to vote. It is unclear whether the constitutional right to vote may be interpreted to include the right to not vote. If challenged, it will up to the superior courts to examine whether compulsory voting violates the Constitution. [A version of this post appeared in the Sakal Times on November 16, 2014]