Applications for the LAMP Fellowship 2026-27 are closed. Shortlisted candidates will be asked to take an online test on January 4, 2026.

The central government has enforced a nation-wide lockdown between March 25 and May 3 as part of its measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. During the lockdown, several restrictions have been placed on the movement of individuals and economic activities have come to a halt barring the activities related to essential goods and services. The restrictions are being relaxed in less affected areas in a limited manner since April 20. In this blog, we look at how the lockdown has impacted the demand and supply of electricity and what possible repercussions its prolonged effect may have on the power sector.

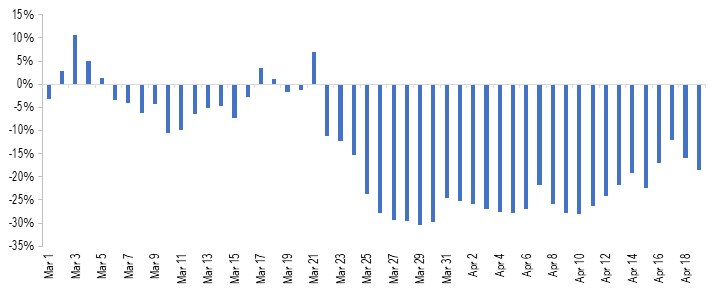

Power supply saw a decrease of 25% during the lockdown (year-on-year)

As electricity cannot be stored in large amount, the power generation and supply for a given day are planned based on the forecast for demand. The months of January and February in 2020 had seen an increase of 3% and 7% in power supply, respectively as compared to 2019 (year-on-year). In comparison, the power supply saw a decrease of 3% between March 1 and March 24. During the lockdown between March 24 and April 19, the total power supply saw a decrease of about 25% (year-on-year).

Figure 1: % change in power supply position between March 1 and April 19 (Y-o-Y from 2019 to 2020)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

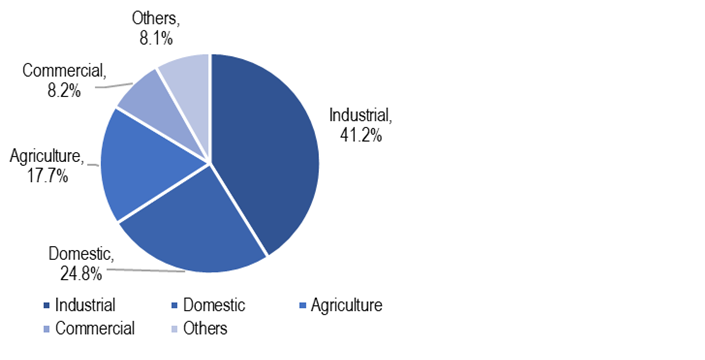

If we look at the consumption pattern by consumer category, in 2018-19, 41% of total electricity consumption was for industrial purposes, followed by 25% for domestic and 18% for agricultural purposes. As the lockdown has severely reduced the industrial and commercial activities in the country, these segments would have seen a considerable decline in demand for electricity. However, note that the domestic demand may have seen an uptick as people are staying indoors.

Figure 2: Power consumption by consumer segment in 2018-19

Sources: Central Electricity Authority; PRS.

Electricity demand may continue to be subdued over the next few months. At this point, it is unclear that when lockdown restrictions are eased, how soon will economic activities return to pre COVID-19 levels. India’s growth projections also highlight a slowdown in the economy in 2020 which will further impact the demand for electricity. On April 16, the International Monetary Fund has slashed its projection for India’s GDP growth in 2020 from 5.8% to 1.9%.

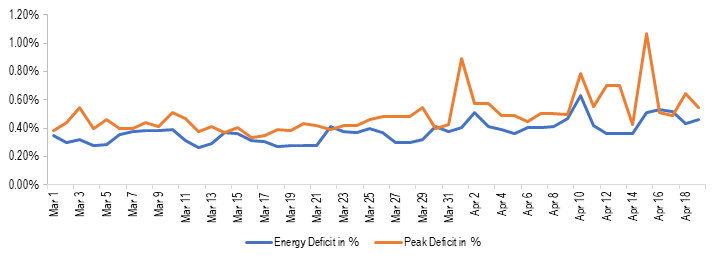

A nominal increase in energy and peak deficit levels

As power sector related operations have been classified as essential services, the plant operations and availability of fuel (primarily coal) have not been significantly constrained. This can be observed with the energy deficit and peak deficit levels during the lockdown period which have remained at a nominal level. Energy deficit indicates the shortfall in energy supply against the demand during the day. The average energy deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.42% while the corresponding figure was 0.33% between March 1 and March 24. Similarly, the average peak deficit between March 25 and April 19 has been 0.56% as compared to 0.41% between March 1 and March 24. Peak deficit indicates the shortfall in supply against demand during highest consumption period in a day.

Figure 3: Energy deficit and peak deficit between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in %)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Coal stock with power plants increases

Coal is the primary source of power generation in the country (~71% in March 2020). During the lockdown period, the coal stock with coal power plants has seen an increase. As of April 19, total coal-stock with the power plants in the country (in days) has risen to 29 days as compared to 24 days on March 24. This indicates that the supply of coal has not been constrained during the lockdown, at least to the extent of meeting the requirements of power plants.

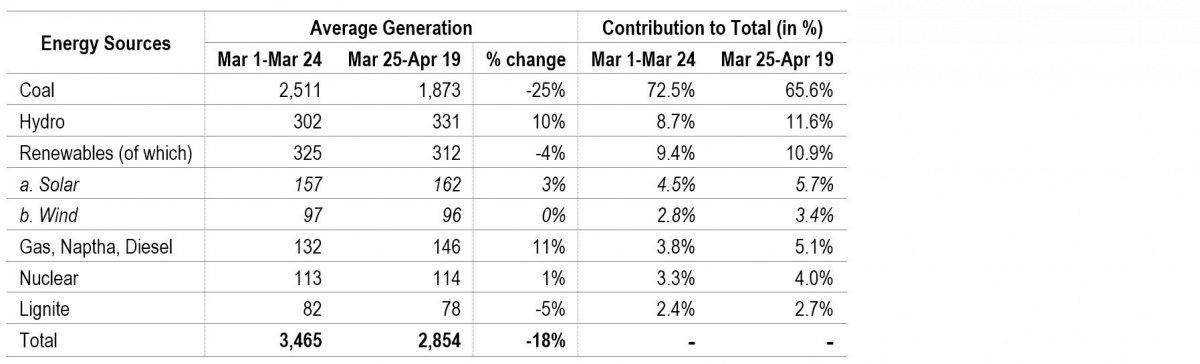

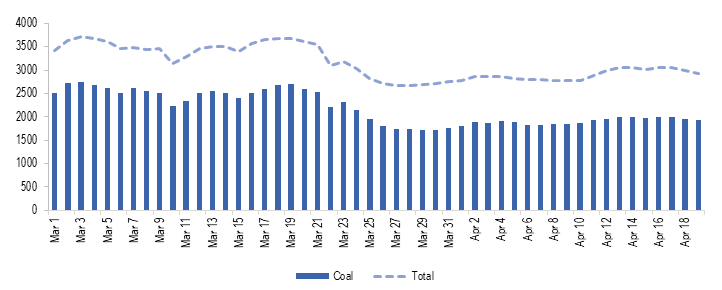

Energy mix changes during the lockdown, power generation from coal impacted

During the lockdown, power generation has been adjusted to compensate for reduced consumption, Most of this reduction in consumption has been adjusted by reduced coal power generation. As can be seen in Table 1, coal power generation reduced from an average of 2,511 MU between March 1 and March 24 to 1,873 MU between March 25 and April 19 (about 25%). As a result, the contribution of coal in total power generation reduced from an average of 72.5% to 65.6% between these two periods.

Table 1: Energy Mix during March 1-April 19, 2020

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

This shift may be happening due to various reasons including: (i) renewable energy sources (solar, wind, and small hydro) have MUST RUN status, i.e., the power generated by them has to be given the highest priority by distribution companies, and (ii) running cost of renewable power plants is lower as compared to thermal power plants.

This suggests that if growth in electricity demand were to remain weak, the adverse impact on the coal power plants could be more as compared to other power generation sources. This will also translate into weak demand for coal in the country as almost 87% of the domestic coal production is used by the power sector. Note that the plant load factor (PLF) of the thermal power plants has seen a considerable decline over the years, decreasing from 77.5% in 2009-10 to 56.4% in 2019-20. Low PLF implies that coal plants have been lying idle. Coal power plants require significant fixed costs, and they incur such costs even when the plant is lying idle. The declining capacity utilisation augmented by a weaker demand will undermine the financial viability of these plants further.

Figure 4: Power generation from coal between March 1, 2020 and April 19, 2020 (in MU)

Sources: Daily Reports; POSOCO; PRS.

Finances of the power sector to be severely impacted

Power distribution companies (discoms) buy power from generation companies and supply it to consumers. In India, most of the discoms are state-owned utilities. One of the key concerns in the Indian power sector has been the poor financial health of its discoms. The discoms have had high levels of debt and have been running losses. The debt problem was partly addressed under the UDAY scheme as state governments took over 75% of the debt of state-run discoms (around 2.1 lakh crore in two years 2015-16 and 2016-17). However, discoms have continued to register losses owing to underpricing of electricity tariff for some consumer segments, and other forms of technical and commercial losses. Outstanding dues of discoms towards power generation companies have also been increasing, indicating financial stress in some discoms. At the end of February 2020, the total outstanding dues of discoms to generation companies stood at Rs 92,602 crore.

Due to the lockdown and its further impact in the near term, the financial situation of discoms is likely to be aggravated. This will also impact other entities in the value chain including generation companies and their fuel suppliers. This may lead to reduced availability of working capital for these entities and an increase in the risk of NPAs in the sector. Note that, as of February 2020, the power sector has the largest share in the deployment of domestic bank credit among industries (Rs 5.4 lakh crore, 19.3% of total).

Following are some of the factors which have impacted the financial situation during the lockdown:

Reduced cross-subsidy: In most states, the electricity tariff for domestic and agriculture consumers is lower than the actual cost of supply. Along with the subsidy by the state governments, this gap in revenue is partly compensated by charging industrial and commercial consumers at a higher rate. Hence, industrial and commercial segments cross-subsidise the power consumption by domestic and agricultural consumers.

The lockdown has led to a halt on commercial and industrial activities while people are staying indoors. This has led to a situation where the demand from the consumer segments who cross-subsidise has decreased while the demand from consumer segments who are cross-subsidised has increased. Due to this, the gap between revenue realised by discoms and cost of supply will widen, leading to further losses for discoms. States may choose to bridge this gap by providing a higher subsidy.

Moratorium to consumers: To mitigate the financial hardship of citizens due to COVID-19, some states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Goa, among others, have provided consumers with a moratorium for payment of electricity bills. At the same time, the discoms are required to continue supplying electricity. This will mean that the return for the supply made in March and April will be delayed, leading to lesser cash in hand for discoms.

Some state governments such as Bihar also announced a reduction in tariff for domestic and agricultural consumers. Although, the reduction in tariff will be compensated to discoms by government subsidy.

Constraints with government finances: The revenue collection of states has been severely impacted as economic activities have come to a halt. Further, the state governments are directing their resources for funding relief measures such as food distribution, direct cash transfers, and healthcare. This may adversely affect or delay the subsidy transfer to discoms.

The UDAY scheme also requires states to progressively fund greater share in losses of discoms from their budgetary resources (10% in 2018-19, 25% in 2019-20, and 50% in 2020-21). As losses of discoms may widen due to the above-mentioned factors, the state government’s financial burden is likely to increase.

Capacity addition may be adversely impacted

As per the National Electricity Plan, India’s total capacity addition target is around 176 GW for 2017-2022. This comprises of 118 GW from renewable sources, 6.8 GW from hydro sources, and 6.4 GW from coal (apart from 47.8 GW of coal-based power projects already in various stages of production as of January 2018).

India has set a goal of installing 175 GW of Renewable Power Capacity by 2022 as part of its climate change commitments (86 GW has been installed as of January 2020). In January 2020, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy observed that India could only install 82% and 55% of its annual renewable energy capacity addition targets in 2017-18 and 2018-19. As of January 2020, 67% of the target has been achieved for 2019-20.

Due to the impact of COVID-19, the capacity addition targets for various sources is likely to be adversely impacted in the short run as:

construction activities were stopped during the lockdown and will take some time to return to normal,

disruption in the global supply chain may lead to difficulties with the availability of key components leading to delay in execution of projects, for instance, for solar power plants, solar PV modules are mainly imported from China, and

reduced revenue for companies due to weak demand will leave companies with less capacity left for capital expenditure.

Key reforms likely to be delayed

Following are some of the important reforms anticipated in 2020-21 which may get delayed due to the developing situation:

The real-time market for electricity: The real-time market for electricity was to be operationalised from April 1, 2020. However, the lockdown has led to delay in completion of testing and trial runs. The revised date for implementation is now June 1, 2020.

UDAY 2.0/ADITYA: A new scheme for the financial turnaround of discoms was likely to come this year. The scheme would have provided for the installation of smart meters and incentives for rationalisation of the tariff, among other things. It remains to be seen what this scheme would be like since the situation with government finances is also going to worsen due to anticipated economic slowdown.

Auction of coal blocks for commercial mining: The Coal Ministry has been considering auction of coal mines for commercial mining this year. 100% FDI has been allowed in the coal mining activity for commercial sale of coal to attract foreign players. However, the global economic slowdown may mean that the auctions may not generate enough interest from foreign as well as domestic players.

For a detailed analysis of the Indian Power Sector, please see here. For details on the number of daily COVID-19 cases in the country and across states, please see here. For details on the major COVID-19 related notifications released by the centre and the states, please see here.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was released on July 30, 2020. It will replace the National Policy on Education, 1986. Key recommendations of the NEP include: (i) redesigning the structure of school curriculum to incorporate early childhood care and education, (ii) curtailing dropouts for ensuring universal access to education, (iii) increasing gross enrolment in higher education to 50% by 2035, and (iv) improving research in higher education institutes by setting up a Research Foundation. In this blog, we examine the current status of education in the country in view of some of these recommendations made by the NEP.

Universal access to Education

The NEP states that the Right to Education Act, 2009 has been successful in achieving near universal enrolment in elementary education, however retaining children remains a challenge for the schooling system. As of 2015-16, Gross Enrolment Ratio was 56.2% at senior secondary level as compared to 99.2% at primary level. GER denotes enrolment as a percent of the population of corresponding age group. Further, it noted that the decline in GER is higher for certain socio-economically disadvantaged groups, based on: (i) gender identities (female, transgender persons), (ii) socio-cultural identities (scheduled castes, scheduled tribes), (iii) geographical identities (students from small villages and small towns), (iv) socio-economic identities (migrant communities and low income households), and (v) disabilities. In the table below, we detail the GER in school education across: (i) gender, and (ii) socio-cultural identities.

Table 1: GER in school education for different gender and social groups (2015-16)

|

Level |

Male |

Female |

SC |

ST |

All |

|

Primary (I-V) |

97.9% |

100.7% |

110.9% |

106.7% |

99.2% |

|

Upper Primary (VI-VIII) |

88.7% |

97.6% |

102.4% |

96.7% |

92.8% |

|

Secondary (IX-X) |

79.2% |

81% |

85.3% |

74.5% |

80% |

|

Senior Secondary (XI-XII) |

56% |

56.4% |

56.8% |

43.1% |

56.2% |

Sources: Educational Statistics at Glance 2018, MHRD; PRS.

Data for all groups indicates decline in GER as we move from primary to senior secondary for all groups. This decline is particularly high in case of Scheduled Tribes. Further, we analyse the reason for dropping out from school education. Data suggests that the most prominent reason for dropping out was: engagement in domestic activities (for girls) and engagement in economic activities (for boys).

Table 2: Major reasons for dropping out (Class 1-12) for 2015-16

|

Reason for dropping out |

Male |

Female |

|

Child not interested in studies |

23.8% |

15.6% |

|

Financial Constraints |

23.7% |

15.2% |

|

Engage in Domestic Activities |

4.8% |

29.7% |

|

Engage in Economic Activities |

31.0% |

4.9% |

|

School is far off |

0.5% |

3.4% |

|

Unable to cop-up with studies |

5.4% |

4.6% |

|

Completed desired level/ Class |

5.7% |

6.5% |

|

Marriage |

|

13.9% |

|

Other reasons |

5.1% |

6.2% |

Note: Other reasons include: (i) timings of educational Institution not suitable, (ii) language/medium of Instruction used unfamiliar, (iii) inadequate number of teachers, (iv) quality of teachers not satisfactory, (v) unfriendly atmosphere at school. For girl students, other reasons also include: (i) non-availability of female teachers, (ii) non-availability of girl’s toilet.

Sources: Educational Statistics at Glance 2018, MHRD; PRS.

The NEP recommends strengthening of existing schemes and policies which are targeted for such socio-economically disadvantaged groups (for instance, schemes for free bicycles for girls or scholarships) to tackle dropouts. Further, it recommends setting up special education zones in areas with significant proportion of such disadvantaged groups. A gender inclusion fund should also be setup to assist female and transgender students in getting access to education.

Increasing GER in Higher Education to 50% by 2035

The NEP aims to increase the GER in higher education to 50% by 2035. As of 2018-19, the GER in higher education in the country stood at 26.3%. Figure 2 shows the trend of GER in higher education over the last few years. Note that the annual growth rate of GER in higher education in the last few years has been around 2%.

Figure 1: GER in Higher Education (2014-15 to 2018-19)

Sources: All India Survey on Higher Education, MHRD; PRS.

Table 3: Comparison of GER (higher education) with other countries

|

Country |

GER (2017-18) |

|

India |

25% |

|

Brazil |

51% |

|

China |

49% |

|

Indonesia |

36% |

|

South Africa |

22% |

|

Pakistan |

9% |

|

Germany |

70% |

|

France |

66% |

|

United Kingdom |

60% |

Sources: UNESCO; PRS.

The NEP recommends that for increasing GER, capacity of existing higher education institutes will have to be improved by restructuring and expanding existing institutes. It recommends that all institutes should aim to be large multidisciplinary institutes (with enrolments in thousands), and there should be one such institution in or near every district by 2030. Further, institutions should have the option to run open distance learning and online programmes to improve access to higher education.

Foundational literacy and numeracy

The NEP states that a large proportion of the students currently enrolled in elementary school have not attained foundational literacy and numeracy (the ability to read and understand basic text, and carry out basic addition and subtraction). It recommends that every child should attain foundational literacy and numeracy by grade three.

Table 4 highlights the results of the National Achievement Survey 2017 on the learning levels of students at Grade 3 in language and mathematics. The results of the survey suggest that only 57% students in Grade 3 are able to solve basic numeracy skills related to addition and subtraction.

Table 4: NAS results on learning level of Grade-3 students

|

Learning level (Grade 3) |

Percentage of students |

|

Ability to read small texts with comprehension (Language) |

68% |

|

Ability to read printed scripts on classroom walls such as poems, posters (Language) |

65% |

|

Solving simple daily life addition and subtraction problems with 3 digits (Mathematics) |

57% |

|

Analyses and applies the appropriate number operation in a situation (Mathematics) |

59% |

Sources: National Achievement Survey (2017) dashboard, NCERT; PRS.

To achieve universal foundational literacy and numeracy, the Policy recommends setting up a National Mission on Foundational Literacy and Numeracy under the MHRD. All state governments must prepare implementation plans to achieve these goals by 2025. A national repository of high-quality resources on foundational literacy and numeracy will be made available on government’s e-learning platform (DIKSHA). Other measures to be taken in this regard include: (i) filling teacher vacancies at the earliest, (ii) ensuring a pupil to teacher ratio of 30:1 for effective teaching, and (iii) training teachers to impart foundational literacy and numeracy.

Effective governance of schools

The Policy states that establishing primary schools in every habitation across the country has helped increase access to education. However, it has led to the development of schools with low number of students. The small size of schools makes it operationally and economically challenging to deploy teachers and critical physical resources (such as library books, sports equipment).

With respect to this observation, the distribution of schools by enrolment size can be seen in the table below. Note that, as of September 2016, more than 55% of primary schools in the country had an enrolment below 60 students.

Table 5: Distribution of schools by enrolment size

|

Strength (Grade) |

Below 30 |

31-60 |

61-90 |

91-120 |

121-150 |

151-200 |

More than 200 |

|

Primary schools (Class 1-5) |

28.0% |

27.5% |

16.0% |

10.3% |

6.3% |

5.6% |

6.4% |

|

Upper primary schools (Class 6-8) |

14.8% |

27.9% |

18.7% |

15.0% |

8.4% |

7.2% |

8.0% |

|

Upper primary schools (Class 1-8) |

5.7% |

11.6% |

13.0% |

12.1% |

10.4% |

13.4% |

33.8% |

Sources: Flash Statistics on School Education 2016-17, UDISE; PRS.

While nearly 80% primary schools had a library, only 1.5% schools had a librarian (as of September 2016). The availability of facilities is better in higher senior secondary schools as compared to primary or upper primary schools.

Table 6: Distribution of schools with access to physical facilities

|

Facilities |

Primary schools (Class 1-5) |

Upper primary schools (Class 1-8) |

Higher senior secondary |

|

Library |

79.8% |

88.0% |

94.4% |

|

Librarian |

1.5% |

4.5% |

34.4% |

|

Playground |

54.9% |

65.5% |

84.3% |

|

Functional computer |

4.4% |

25.2% |

46.0% |

|

Internet connection |

0.9% |

4.2% |

67.9% |

Sources: Flash Statistics on School Education 2016-17, UDISE; PRS.

To overcome the challenges associated with development of small schools, the NEP recommends grouping schools together to form a school complex. The school complex will consist of one secondary school and other schools, aanganwadis in a 5-10 km radius. This will ensure: (i) adequate number of teachers for all subjects in a school complex, (ii) adequate infrastructural resources, and (iii) effective governance of schools.

Restructuring of Higher Education Institutes

The NEP notes that the higher education ecosystem in the country is severely fragmented. The present complex nomenclature of higher education institutes (HEIs) in the country such as ‘deemed to be university’, ‘affiliating university’, ‘affiliating technical university', ‘unitary university’ shall be replaced simply by 'university'.

According to the All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19, India has 993 universities, 39,931 colleges, and 10,725 stand-alone institutions (technical institutes such as polytechnics or teacher training institutes).

Table 7: Number of Universities in India according to different categories

|

Type of university |

Number of universities |

|

Central University |

46 |

|

Central Open University |

1 |

|

Institutes of National Importance |

127 |

|

State Public University |

371 |

|

Institution Under State Legislature Act |

5 |

|

State Open University |

14 |

|

State Private University |

304 |

|

State Private Open University |

1 |

|

Deemed University- Government |

34 |

|

Deemed University- Government Aided |

10 |

|

Deemed University- Private |

80 |

|

Total |

993 |

Sources: All India Survey on Higher Education 2018-19; PRS.

The NEP recommends that all HEIs should be restructured into three categories: (i) research universities focusing equally on research and teaching, (ii) teaching universities focusing primarily on teaching, and (iii) degree granting colleges primarily focused on undergraduate teaching. All such institutions will gradually move towards full autonomy - academic, administrative, and financial.

Setting up a National Research Foundation to boost research

The NEP states that investment on research and innovation in India, at only 0.69% of GDP, lags behind several other countries. India’s expenditure on research and development (R&D) in the last few years can be seen in the figure below. Note that the total investment on R&D in India as a proportion of GDP has been stagnant at around 0.7% of GDP. In 2018-19, the total expenditure on R&D in India was Rs 1,23,848 crore. Of this, Rs 72,732 crore (58%) of expenditure was by government, and the remaining (42%) was by private industry.

Figure 2: R&D Expenditure in India (2011-12 to 2018-19)

Sources: S&T Indicators Table 2019-20, Ministry of Science and Technology, March 2020; PRS.

Figure 3: Comparison of R&D expenditure in India with other countries (2017)

Sources: S&T Indicators Table 2019-20, Ministry of Science and Technology, March 2020; PRS.

To boost research, the NEP recommends setting up an independent National Research Foundation (NRF) for funding and facilitating quality research in India. The Foundation will act as a liaison between researchers and relevant branches of government as well as industry. Specialised institutions which currently fund research, such as the Department of Science and Technology, and the Indian Council of Medical Research, will continue to fund independent projects. The Foundation will collaborate with such agencies to avoid duplication.

Digital education

The NEP states that alternative modes of quality education should be developed when in-person education is not possible, as observed during the recent pandemic. Several interventions must be taken to ensure inclusive digital education such as: (i) developing two-way audio and video interfaces for holding online classes, and (ii) use of other channels such as television, radio, mass media in multiple languages to ensure reach of digital content where digital infrastructure is lacking.

In this context, we analyse: (i) the availability of computer and internet across households in India, and (ii) ability to use computer or internet by persons in the age group of 5-14. As of 2017-18, the access to internet and computer was relatively poor in rural areas. Only 4.4% of rural households have access to a computer (excludes smartphones), and nearly 15% have access to internet facility. Amongst urban households, 42% have access to internet.

Table 8: Access to Computer and Internet across households (2017-18)

|

Access to ICT |

Rural |

Urban |

Overall |

|

Households having computer |

4.4% |

23.4% |

10.7% |

|

Households having internet facility |

14.9% |

42.0% |

23.8% |

Note: Computer includes desktop, laptop, notebook, tablet. It does not include smartphone.

Sources: Household Social Consumption on Education (2017-18), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, July 2020; PRS.

Table 9: Ability to use Computer and Internet across persons in the age group 5-14 (2017-18)

|

Ability to use ICT |

Rural |

Urban |

Overall |

|

Ability to use computer |

5.1% |

21.3% |

9.1% |

|

Ability to use internet |

5.1% |

19.7% |

8.8% |

Note: Ability to use computer means to be able to carry out any of the tasks such as: (i) copying or moving a file/folder, (ii) sending emails, (iii) transferring files between a computer and other devices, among others. Ability to use internet means to be able to use the internet browser for website navigation, using e-mail or social networking applications.

Sources: Household Social Consumption on Education (2017-18), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, July 2020; PRS.

Public spending on education to be increased to 6% of GDP

The recommendation of increasing public spending on Education to 6% of GDP was first made by the National Policy on Education 1968 and reiterated by the 1986 Policy. NEP 2020 reaffirms the recommendation of increasing public spending on education to 6% of GDP. In 2017-18, the public spending on education (includes spending by centre and states) was budgeted at 4.43% of GDP.

Table 10: Public spending on Education (2013-2018)

|

Year |

Public expenditure (Rs crore) |

% of GDP |

|

2013-14 |

4,30,879 |

3.84% |

|

2014-15 |

5,06,849 |

4.07% |

|

2015-16 |

5,77,793 |

4.20% |

|

2016-17 |

6,64,265 |

4.32% |

|

2017-18 |

7,56,945 |

4.43% |

Sources: 312th Report, Standing Committee on Human Resource Development, March 2020; PRS.

Figure 4: Comparison of public spending on Education in India with other countries as % of GDP (2015)

Sources: Educational Statistics at Glance 2018, MHRD; PRS.

In the figure below, we look at the disparities within states in education spending. In 2020-21, states in India have allocated 15.7% of their budgeted expenditure towards education. States such as Delhi, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra have allocated more than 18% of their expenditure on Education for the year 2020-21. On the other hand, Telangana (7.4%), Andhra Pradesh (12.1%) and Punjab (12.3%) lack in spending on education, as compared to the average of states.

Figure 5: Budgeted allocation on Education (2020-21) by states in India

Note: AP is Andhra Pradesh, UP is Uttar Pradesh, HP is Himachal Pradesh and WB is West Bengal.

Sources: Analysis of various state budget documents; PRS.

For a detailed summary of the National Education Policy, see here.