The long title of this year’s Finance Bill states that it “gives effect to the financial proposals of the Central Government for the financial year 2017-18”. This is because the Finance Bill typically includes provisions that give effect to the imposition of a tax or a change in existing tax rates — such as a lowering of income tax, or changes to corporate tax, customs or excise duties. Since the Finance Bill is a Money Bill, it only needs the approval of Lok Sabha, and Rajya Sabha may only make recommendations. If Rajya Sabha does not pass the Bill within 14 calendar days, it is deemed to be passed. This year, the Finance Bill has been passed by Lok Sabha with not only changes to applicable taxes, but also structural changes to institutions and sectors.

This, however, is not the first time that the Finance Bill has proposed legislative changes that are unrelated to taxation. In earlier years, the Finance Bill has envisaged substantive provisions relating to the creation of an independent agency to manage government debt, the Monetary Policy Committee to target inflation, and the merging of the Forward Markets Commission with the Securities regulator. MPs from both Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha have objected to such structural provisions being included in the Finance Bill. During the debate on the Finance Bill in 2015, Trinamool Congress MP from Dum Dum, Saugata Roy, complained that “these are drastic amendments and bundle of amendments are equivalent to that of a new Bill. These are separate legislations and cannot be part of a Money Bill as Lok Sabha has exclusive power to debate and vote on Money Bills. The Rajya Sabha unfortunately does not have the power.”

The Finance Bill, 2017 allows the central government to specify the appointments, tenure, removal, and reappointment of chairpersons and members of Tribunals through Rules. Currently, these provisions are specified in the parent laws establishing these Tribunals. The fundamental issue here is whether it is appropriate to delegate such matters to the government through Rules. Typically, a Bill passed by Parliament includes the broad regulatory framework and principles governing the sector, and allows the government to specify the details of implementation through Rules. The idea behind delegating Rulemaking to the government is to address the need for expediency and flexibility in implementation of laws. While a Bill requires parliamentary approval in order to be enforced, Rules do not. Giving the government the power to make Rules regarding the appointment, removal, and reappointment of members on a Tribunal lowers the threshold of parliamentary scrutiny.

Tribunals are quasi-judicial bodies that are headed by a senior member of the judiciary, such as a judge of the Supreme Court or Chief Justice of a High Court. There could be a conflict of interest if the government were to be a litigant before a Tribunal, while also determining the appointment of its members and presiding officer. Tribunals affected by the Finance Bill include those before which the central government could be a party to disputes — such as those related to Income Tax, Railways, administrative matters, and the Armed Forces Tribunal. In 2014, the Supreme Court, while examining provisions related to the National Tax Tribunal, had held that Appellate Tribunals have powers and functions similar to that of High Courts, and hence matters related to the appointment and reappointment of their members must be free from executive involvement.

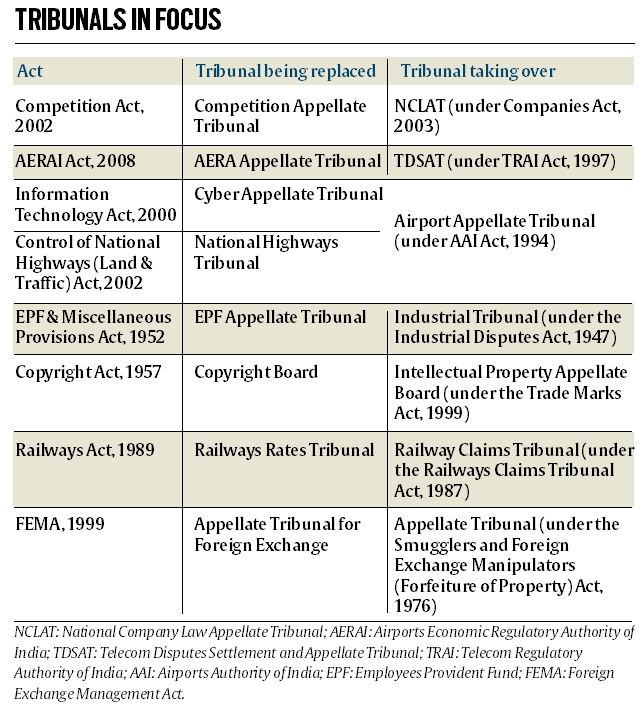

The amendments to the Finance Bill also replace certain existing Tribunals and transfer their functions to other Tribunals. The rationale for this overhaul has not been stated. For example, the Airports Economic Regulatory Authority Appellate Tribunal has been replaced by the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT). It is unclear whether TDSAT, which primarily deals with telecom disputes, will have the expertise to adjudicate matters relating to the pricing of airport services. Similarly, it is questionable whether the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal, which will replace the Competition Appellate Tribunal, will have the expertise to deal with matters relating to anti-competitive practices.

The Finance Bill allows anonymous donations to political parties through electoral bonds. It also removes existing limits on the percentage of profits that a company can donate to political parties. The broad policy question is how to strike a balance between transparency versus anonymity in political funding. Anonymity in political funding may be desirable to protect donors from harassment from rival political parties. On the other hand, transparency in donations to political parties provides information on interested entities that financially support political parties. Other structural changes made by the Finance Bill include the creation of the Payments Regulatory Board. It also makes Aadhaar mandatory when applying for a Permanent Account Number (PAN), or filing Income Tax returns. Every person holding a PAN is also required to provide his Aadhaar number, else the PAN will be invalid.

The lawmaking process has evolved over the years to ensure detailed scrutiny, deliberations, expert feedback and public consultation on legislative proposals of the government through the establishment of Parliamentary Standing Committees. While demands for grants of various ministries in the Union Budget are examined by Parliamentary Standing Committees during the Budget session, the tax proposals in the Finance Bill are not. Therefore, such instances where structural changes to laws are included in the Finance Bill bypass institutional checks and balances that ensure the role of both Houses of Parliament in lawmaking. The question is whether structural changes should be enacted without going through the established Standing Committee scrutiny processes that ensure a careful assessment of the impact of legislative proposals of the government and ensure public engagement and rigour in the lawmaking process.